2023 marks the 60th anniversary of mandated newborn screening (NBS). NBS — having infants undergo a heel prick within 24-48 hours of birth to collect a few drops of blood, which blood is then tested for dozens of disorders — began when Dr. Robert Guthrie devised a blood test that could detect Phenylketonuria (PKU). In 1963, Massachusetts was the first state to mandate screening for PKU for all babies born in the commonwealth; between 1963 and 1985, all states mandated NBS in some form.

By the early 2000s, however, some states screened for as many as 50 conditions while other states screened for as few as four conditions. This led the Health Resources and Services Administration to ask the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) to develop a list of recommended conditions that all states should screen for at birth. In 2003, the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) formed to advise the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary on NBS. In 2005, ACMG determined a list of 29 core NBS conditions in partnership with ACHDNC that formed the federally Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). The RUSP was ultimately implemented by HHS in 2010, and there are currently 63 disorders on the RUSP (37 core conditions and 26 secondary conditions). The ACHDNC continues to serve as an advisory committee to the HHS Secretary and recommends conditions to be added to, or removed from, the federal RUSP.

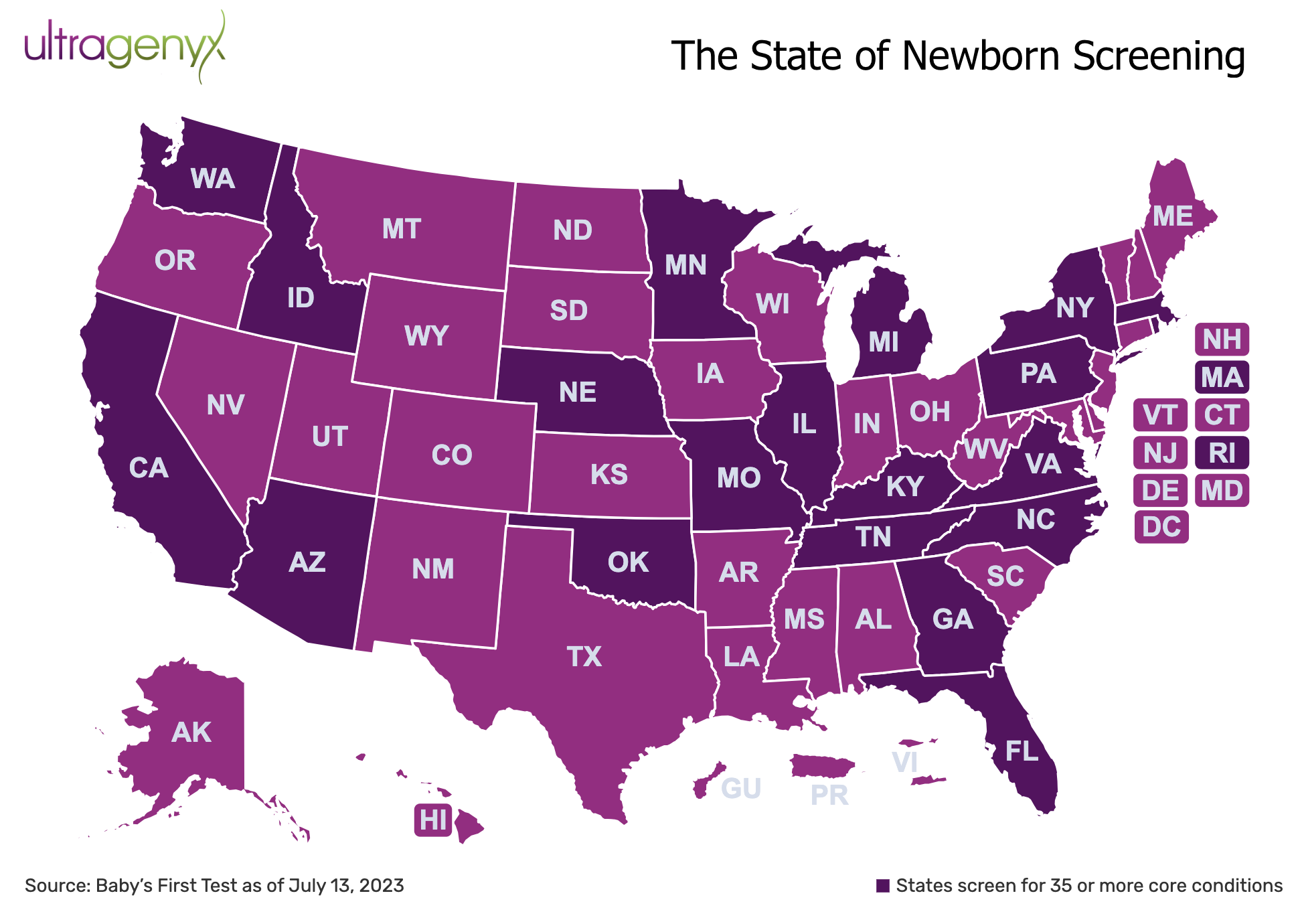

The implementation of the RUSP has resulted in tremendous progress and a trend toward consistency across states; by 2011, all states screened for at least 26 core conditions. By 2022, all states screened for at least 31 core conditions and 27 states (representing 64% of births) screened for at least 35 core conditions.

Newborn screening (NBS) is one of the most successful public health programs of all time, but it has limitations that must be addressed.

Notwithstanding that NBS is one of the most successful public health programs of all time, it has limitations that need to be addressed to ensure continued improvement in the future. One limitation of the current NBS system is that the process of adding a condition to the RUSP can take years; it is not uncommon for it to take five years or more. Last year, the ACHDNC indicated that they only have the resources to review two conditions per year. Considering there are 63 conditions on the RUSP and approximately 10,000 known rare diseases, reviewing two conditions per year is nowhere near enough.

Another limitation is that once a condition is added to the federal RUSP, it can take many more years for states to add and implement that recommended NBS condition in their state-based NBS system. For example, mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I) was added to the RUSP in 2016; it has been seven years since MPS I was added to the RUSP and all 50 states still do not screen for MPS I. These lengthy timelines have real-world consequences.

One of the biggest consequences of the limitations under the current NBS system is that there is a basic lack of equity; a baby’s health outcomes can differ depending on which state they are born in if one state screens for a certain condition that another state does not. There are countless examples of this very phenomenon occurring, and it is unacceptable.

The federal government needs to provide sufficient resources to the ACHDNC as well as reauthorize the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act to ensure adequate funding for NBS programs in the states.

Newborn screening alone is insufficient to keep pace with science; political leadership is needed to supplement NBS with genetic testing

Newborn screening alone is insufficient to keep pace with science; political leadership is needed to supplement NBS with genetic testing. There are approximately 10,000 known rare diseases; the RUSP accounts for 63 of them. Clearly, many diseases capable of being diagnosed are not addressed under the current system.

Since the sequencing of the human genome, we have the power to identify one of the many genes that can be defective in a child. When we see a child with these diseases, we have to be able to do genetic testing to help figure out what they have. Instead of spending 5 to 7 years or longer in a diagnostic odyssey, we need to support genetic tests for patients with symptoms so that they can get diagnosed promptly and participate in clinical trials or receive better treatment for their conditions. It’s unconscionable that we leave patients with rare diseases undiagnosed because we’re not supporting genetic testing for those diseases.

Several recent articles have highlighted the importance of genetic testing (specifically, whole genome sequencing) to diagnose rare diseases, even arguing that this type of testing be provided to all newborns at birth. Indeed, there are many pilots underway to examine genetic testing in healthy newborns at birth: BeginNGS; BabySeq; and Guardian to name a few.

But, there is an intermediate step that can be taken now; Congress can and should reintroduce and pass the Precision Medicine Answers for Kids Today Act.

At a time when it is difficult to find bipartisan issues to advance, being able to provide quick and accurate diagnoses to sick children to improve their health outcomes should be a no-brainer.

This legislation would authorize the Department of Health and Human Services to enter into agreements with up to 15 states to conduct three-year demonstration projects to provide Medicaid coverage of genetic and genomic testing for children who: (1) have a positive result from a newborn screening program; (2) have one or more neurodevelopmental or congenital anomalies; (3) are experiencing developmental delay or intellectual disability; (4) are having seizures; (5) have been referred or admitted to a pediatric or neonatal intensive care unit for a chronic or undiagnosed disease; (6) have been seen by at least one medical specialist for such chronic or undiagnosed disease; or (7) are suspected by at least one healthcare provider to have a neonatal- or pediatric-onset genetic disease.

The legislation has two Democratic members of Congress on board; Republican leadership is also needed. Who will stand up and fight for these children?

At a time when it is difficult to find bipartisan issues to advance, being able to provide quick and accurate diagnoses to sick children to improve their health outcomes should be a no-brainer.

Lisa M. Kahlman is executive director of public policy and public affairs at Ultragenyx

To learn more, visit: https://newbornscreening.ultragenyx.com/