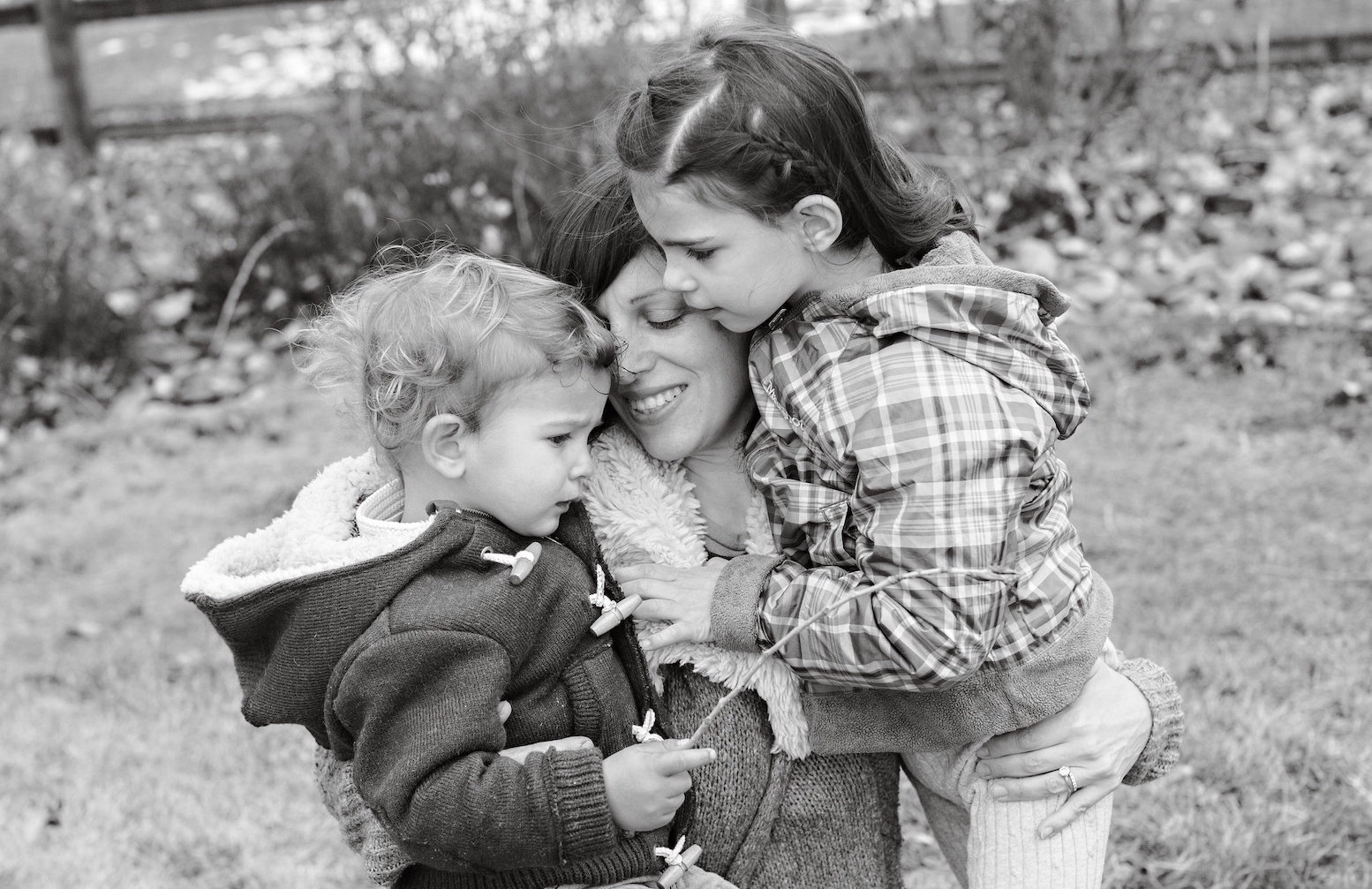

At age six, Mila Makovec was diagnosed with Batten disease, a rare and progressive neurological disorder. Upon learning that her daughter’s disease had no cure, Julia Vitarello started Mila’s Miracle Foundation to initiate and fund novel treatments. Working alongside Dr. Timothy Yu and his team at Boston Children’s Hospital to develop a truly personalized treatment for Mila, Julia found herself on the front lines of ultrarare drug development, helping to pioneer a movement for “n-of-1″ therapies – treatments designed for one person’s unique genetic mutation.

In a remarkable collaboration between scientists, physicians, drug developers, foundations and regulators, a novel medicine was created, tested and delivered in just one year from Mila’s diagnosis. Mila became the first person in the world to receive a drug customized for just one person. It was named milasen.

While Mila would eventually succumb to her condition, milasen improved her symptoms and her quality of life. The 2019 publication of this effort in the New England Journal of Medicine drew international attention as the first example of individualized genomic medicine, giving new hope to patients with ultrarare conditions.

In 2021, Julia and Dr. Yu launched the N=1 Collaborative as the first international hub for individualized medicines for rare diseases. I sat down with Julia to discuss the organization and their “platform approach” to developing personalized treatments.

Jessica: What made you realize your efforts to save Mila could be turned into a scalable process for rare disease research and development?

Julia: When I was told my previously healthy, outgoing daughter Mila would lose all of her abilities and die, initially I was on a race against time to save her life. It just happened that her mutation and disease were amenable to an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO), a type of treatment that can modify gene expression and mRNA splicing in the nervous system.

Since Mila began treatment, I have spoken with hundreds of people in the field and it hit me that this individualized approach to treating genetic conditions could help solve the global health crisis of rare disease. If we could target Mila’s specific mutation with an ASO, as more and more programable modalities were developed, why couldn’t we do the same for tens or hundreds of thousands of children across rare diseases?

Jessica: Who are the participants in the N=1 Collaborative and what are your immediate goals?

Julia: Hundreds of people primarily from academia and industry have joined the N1C effort to share data, knowledge and experience on individualized medicines. We have workgroups focusing on rethinking the drug development process, including data and safety, outcome measures and regulatory strategy. Our mission is to make individualized medicines like milasen routine worldwide.

Our mission is to make individualized medicines routine worldwide.

The data safety group is working on building a database of preclinical and clinical data to support the development of new individualized treatments. We’re also developing guidelines on which diseases, mutations and patients are amenable to this approach. We’re devising a plan for how to think about outcome measures and how to bring academic institutions on board with this new concept.

Jessica: What about the current drug development system needs to change to enable the future of individualized medicine?

Julia: Traditionally, we have created drugs for large cohorts of people who all share one disease. Now, we have the technology to find the underlying genetic cause of disease and design a treatment to target it, independent of the number of people who could benefit.

Ethically, we must pivot and rethink the drug development process for this new paradigm.

Today, we have the science to help children like Mila and we have millions of rare patients in need, but we don’t have a framework or system that allows for access. Ethically, we must pivot and rethink the drug development process for this new paradigm. That’s what motivated me, together with Tim Yu and others to launch the N=1 Collaborative.

Jessica: What has most surprised you as you launched the N=1 Collaborative?

Julia: There have only been a few handfuls of treatments like Mila’s over the past five years and the information gained from each is invaluable. It seems obvious to me that the way to make this individualized approach routine was for everyone working on these treatments to share their knowledge, experience, processes and data to empower an entire field of people to do this. Unfortunately, there are still many working in silos who believe that only a few experts are capable of doing this work, which has been difficult to watch.

On the other hand, I have been pleasantly surprised at how many people around the world are joining the N1C to say, “I’d like to do this, too. Please help me learn.” Many people have even shifted their careers as a result and now want to focus on individualized genetic treatments.

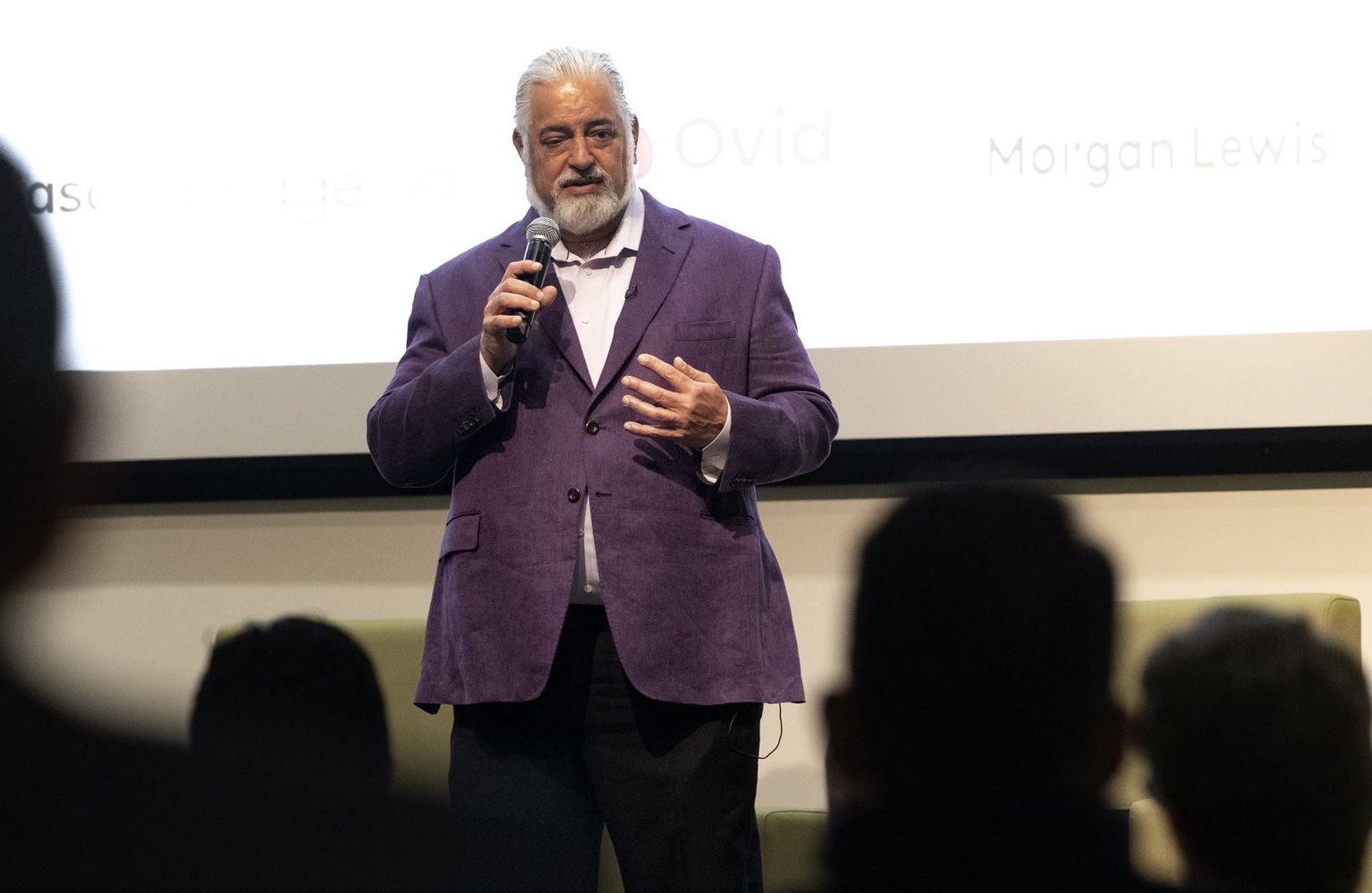

Photo: Julia Vitarello speaks to an audience of biotech leaders in 2022

Jessica: What kinds of questions are the parents of children with rare diseases asking you and the team today?

Julia: Parents want to know if their child’s disease is amenable to an ASO treatment. The Yu Lab fields requests and responds to every family directly, as does n-Lorem Foundation, a non-profit organization developing personalized ASO treatments for patients with ultrarare diseases. As ASOs are the only tool in the toolbox for now, most cases are not amenable or not accepted. Right now, there aren’t many places parents can go to get that information.

The N1C is trying to enable more people to be able to do this work safely and rapidly to create a worldwide network to meet the increasingly enormous demand.

Parents also want to find a principal investigator (the person responsible for preparing and carrying out the clinical trial protocol) and if they already have one, they want that team to learn the best practices around safe ASO design and trials. The N1C is trying to enable more people to be able to do this work safely and rapidly to create a worldwide network to meet the increasingly enormous demand.

Jessica: What challenges remain for this potential treatment path?

Julia: We inherited a system of drug development that was appropriate for developing a single drug for many thousands of people; Mila’s story points to a near future with thousands of drugs each designed for one or just a small number of people. We need a new paradigm – instead of a product approval, we must move toward a process approval to enable access.

What if the product were not a drug but a process with a programmable component?

Rare childhood diseases are a massive global health crisis that we have not even scratched the surface of. At the current rate, some estimate it will take 2,000 years to create drugs for all rare diseases. We now have a programmable approach, but very few children have been treated with this approach because the requirements are so disproportionately high.

The risk of not treating a child like Mila is black and white – she will lose all of her abilities and die. Like with every novel drug, there are risks associated with treatment, and the N1C is helping de-risk this by developing best practices based on what we know so far. However, we won’t get there unless everyone in the field shares knowledge and data and we have a clear and rapid path to treating as many children as possible – learning, improving and continuing to treat. Having to climb Mt. Everest each time is not ethically correct when the science exists today.

Jessica: When you think about the work of the N=1 Collaborative, what do you hope the future will look like in 5, 10 years?

Julia: If we’re successful as a field, individualized medicine centers around the world will diagnose children at birth, or even in utero, and within just a few months develop and deliver a genetic treatment tailored to their underlying cause of disease – and the cost will be covered by insurance. These families will not need to raise millions of dollars and become drug developers, and these children can grow up without ever knowing the devastation of disease.